Law and Order "a Death in the Family"

| "A Death in the Family" | |

|---|---|

Encompass of Batman #428 (October 18, 1988) | |

| Publisher | DC Comics |

| Publication date | August – November 1988 |

| Genre |

|

| Title(s) | Batman #426–429 |

| Master character(due south) |

|

| Creative team | |

| Writer(s) | Jim Starlin |

| Penciller(south) | Jim Aparo |

| Inker(s) | Mike DeCarlo |

| Letterer(due south) | John Costanza |

| Colorist(south) | Adrienne Roy |

| Editor(s) | Dennis O'Neil |

| 2011 edition | ISBN 1401232744 |

"A Death in the Family" is a 1988 storyline in the American comic volume Batman, published past DC Comics. Information technology was written by Jim Starlin and penciled past Jim Aparo, with cover fine art by Mike Mignola. Serialized in Batman #426–429 from August to Nov 1988, "A Death in the Family" is considered ane of the most important Batman stories for featuring the death of his sidekick Robin at the hands of his archenemy, the Joker.

Jason Todd, the second graphic symbol to assume the Robin persona, was introduced in 1983 to supplant Dick Grayson, who was unavailable for use at the time. Todd became unpopular among readers after 1986, as writers began to characterize him as rebellious and impulsive. Editor Dennis O'Neil was considering having Todd revamped or written out of Batman when he recalled a 1982 Saturday Dark Live sketch in which Eddie Potato encouraged viewers to call the evidence if they wanted him to boil a lobster on air. Inspired to orchestrate a like stunt, DC fix a 900 number voting arrangement to allow fans to decide Todd's fate.

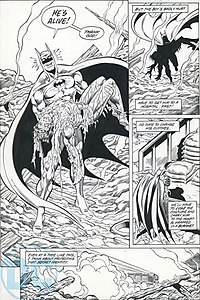

"A Death in the Family" begins when Batman relieves Todd of his offense-fighting duties. Todd travels to the Middle East to find his biological mother, only is kidnapped and tortured by the Joker. Batman #427 ends with the Joker blowing Todd up in a warehouse. Starlin and Aparo prepared ii versions of the following issue: i that would be published if readers voted to have Todd survive, and some other if he was to be killed. A narrow bulk voted in favor of the latter, and Batman #428 features Batman discovering Todd's lifeless body in the warehouse ruins. The storyline ends when Batman and Superman end the Joker from killing the United Nations General Assembly.

The story was controversial and widely publicized; despite Todd'south unpopularity, DC faced backlash for the conclusion to kill one of its well-nigh iconic characters. Todd's demise had a lasting effect on Batman stories, Batman's failure to salve him pushing the comic book mythos in a darker direction. Tim Drake succeeded Todd equally Robin in 1989, and Todd was resurrected as the Red Hood in the "Under the Hood" (2004–2006) storyline. "A Death in the Family" remains a popular story among readers and has been reprinted in trade paperback grade since its initial publication. Plot elements take been incorporated into Batman films, television serial, and video games. An animated interactive flick adaptation, Batman: Decease in the Family, was released in 2020.

Publication history [edit]

Background [edit]

[The fans] did detest [Jason Todd]. I don't know if information technology was fan craziness—perchance they saw him every bit usurping Dick Grayson's position... It may be that something was working in the writers' minds, probably on a subconscious level. They fabricated [Todd] a trivial bit more disagreeable than his predecessor had been. He did become unlikeable and that was non whatsoever doing of mine.

Dennis O'Neil on Jason Todd's unpopularity[ane]

Robin, the boyish sidekick of the DC Comics superhero Batman, first appeared in Detective Comics #38 in April 1940. He was introduced by Bob Kane, Bill Finger, and Jerry Robinson to give Batman a companion and increase his appeal to children.[2] The original Robin, Dick Grayson, made regular appearances in Batman publications from 1940 until the early 1980s, when Marv Wolfman and George Pérez began including him in the New Teen Titans comics.[3] Every bit this fabricated Grayson unavailable to the Batman comics, Batman writer Gerry Conway and artist Don Newton introduced Jason Todd in Batman #357 (March 1983).[four] Wolfman and Pérez had Grayson gear up bated the Robin identity and become the independent superhero Nightwing in Teen Titans, while Todd became Robin in the Batman family of comics.[4] [5]

Originally, Todd's origin story was near identical to Grayson's; like Grayson, Todd was depicted as the son of circus acrobats who became Batman'due south sidekick after his parents were murdered.[5] Dennis O'Neil, who wrote Batman and Detective Comics throughout the 1970s and became the Batman group editor in 1986, said that Conway and Newton "[weren't] worried about creating a new grapheme. I retrieve they idea, 'Nosotros've got to have a Robin in the series and so let's go with the tried and true. This Robin has worked for so many years, and so let'southward exercise him once more.'"[i] Following the Crunch on Space Earths (1985–1986) crossover event, which rebooted the DC Universe,[a] Batman writer Max Allan Collins was asked to reintroduce Todd.[4] Batman #408 (June 1987) began a iv-result story by Collins and creative person Chris Warner that reimagined Todd every bit a street delinquent whom Batman attempts to reform.[6]

The revamped Todd was unpopular among readers, who disliked his rebellious, impulsive nature.[vii] A scene in Batman #424 (June 1988) in which Todd seemingly breaks Batman's no-kill rule and lies about it was particularly controversial.[8] Later on Collins quit over artistic differences, writer Jim Starlin and penciler Jim Aparo took over Batman.[4] Starlin did not like Todd and initially avoided featuring him, but began to employ him in stories at the request of O'Neil. Starlin "decided to play on that dislike" in his stories.[9] By 1988, the Batman creative team knew Todd presented a trouble that needed to be resolved.[i]

Development [edit]

Jim Starlin (pictured in 2008) proposed killing Robin 6 months before he was asked to write "A Death in the Family".

O'Neil decided that Todd either needed another personality revamp or to exist written out of Batman.[ten] Around that time, DC was planning to publish a comic promoting HIV/AIDS education, and requested that writers submit suggestions for characters to kill off from AIDS. Starlin filled the proffer box with proposals to kill off Todd, merely DC staff rejected the idea after realizing all the papers had Starlin's handwriting.[xi] DC president Jenette Kahn wanted to address Todd's unpopularity.[four] O'Neil and Kahn attended an editorial retreat, where O'Neil recalled a 1982 Saturday Night Live sketch in which Eddie Murphy encouraged viewers to telephone call one of two 900 numbers if they wanted him to eddy a lobster on air. The sketch garnered widespread publicity and about 500,000 viewers called in.[12] O'Neil proposed a similar stunt involving one of the DC characters, which Kahn institute intriguing.[1] [thirteen]

O'Neil decided that Todd was "the logical candidate to be in peril", as he was unpopular and placing him in such a situation would have massive ramifications.[1] "Nosotros didn't want to waste matter it on anything minor", he said. "Whether Firestorm'south boots should be red or yellow ... This had to be important. Life or death stuff."[13] Kahn added that they wanted to allow fans to have input in what to exercise with Todd, rather than "autocratically" writing him out and replacing him.[4] The idea of having fans telephone call to influence the creative process was a novel concept at the time, and DC'south sales and marketing vice president Bruce Bristow described setting up the numbers every bit the most hard part of the projection. Sales managing director John Pope began calling AT&T to secure the two 900 numbers on October 1, 1987; information technology took him until March 1988 to reserve them.[fourteen]

Six months after Starlin proposed killing Todd, O'Neil asked him to start working on a potential story.[11] Starlin decided to have the Joker murder Todd, inspired by The Nighttime Knight Returns (1986), a limited series by Frank Miller that featured Batman retiring after the Joker kills Robin.[nine] Starlin wrote scripts for a six-result story,[4] and the decision was made to combine the first four across 2 problems to speed up the story because fans were participating.[xiv] Aparo, inker Mike DeCarlo, and colorist Adrienne Roy provided the fine art, and banana editor Dan Raspler suggested Mike Mignola equally the storyline'south comprehend creative person.[4] Batman #427 features Batman arriving at a warehouse where Todd is imprisoned simply as it explodes. On the back cover, an advertisement featured Batman conveying a severely wounded Todd. Readers were warned that Todd could dice of his injuries, but that they could "prevent it with a telephone call". Two 900 numbers were given: one (1-(900) 720-2660) which would let Robin live, and another (1-(900) 720-2666) which would cause him to die. The numbers were activated for 35 hours in the United States and Canada from 9:00a.m. Eastern Standard Time on September 15, 1988.[xiii] [4]

Artwork from the unpublished (left) and published (correct) versions of Batman #428, showing the two planned scenarios. Considering readers voted to kill Todd, the left folio went unpublished. Art by Jim Aparo, Mike DeCarlo, and Adrienne Roy.

Starlin and the artists prepared two versions of Batman #428, depending on the outcome.[11] Every bit O'Neil stated, "It really could have gone either way. We prepared two choices of balloons. We had alternate panels. We had everything set upwards so that the two outcomes could be achieved with a minimum of changes. Nosotros prepared for either state of affairs."[fourteen] Raspler explained that Aparo prepared iii alternate pages and several panels with static images that could be easily rearranged.[four] O'Neil voted to allow Todd live, every bit he felt killing the character would complicate his job as an editor,[xiv] and Starlin was unable to vote because he was in Mexico at the time.[11] O'Neil and Raspler checked the results every 90 minutes.[fourteen] DC executive editor and vice president Dick Giordano expected readers to vote in favor of Todd's survival; O'Neil believed they would vote for his death to meet if DC would follow through.[x]

The poll received x,614 votes and 5,343 voted for Todd's death over v,271 for his survival—a margin of just 72 votes.[4] [14] Although Kahn dispelled rumors that the process was rigged in favor of Todd's demise,[4] O'Neil said it was possible many votes favoring Todd's expiry came from a single person. He recalled hearing that "a lawyer programmed his Macintosh to punch the killing number every few minutes", but had no prove.[x] O'Neil canceled a party he planned to throw once the verdict was in and decided to go along the effect surreptitious until Batman #428 was shipped. O'Neil did not tell his wife, Starlin, or Aparo.[14] Starlin had expected Todd to die just was surprised by how close the vote was.[11] Production manager Bob Rozakis supervised Roy equally she finished coloring, and and so had Steve Bove take the "real" Batman #428 to terminate it in the secrecy of his basement.[xiv]

Publication [edit]

"A Death in the Family unit" was published when Batman was surging in popularity. Following the success of The Dark Knight Returns and the "Year One" (1987) storyline, monthly sales for Batman were at their highest level since the early 1970s, and Tim Burton's Batman (1989) feature film was in production.[4] DC announced "A Death in the Family" shortly later on the release of the critically acclaimed graphic novel Batman: The Killing Joke in 1988; according to author Chris Sims, the Batman letter column immediately "broke out into argue" over whether Todd should live or dice.[8]

Batman #426, the outset issue of "A Expiry in the Family", was released on August 23, 1988, and Batman #427, the second, was released 2 weeks later, on September 6.[iv] Fans voted to make up one's mind Todd's fate between September xv and 16, 1988, and Batman #428, which featured Todd's death, was released on October 18, 1988.[4] The storyline concluded with Batman #429, on November 29, 1988.[4] The final ii issues contained a guest appearance from Superman.[4] Subsequently the get-go three issues of "A Decease in the Family" sold out, DC compiled the storyline into a trade paperback in time for the 1988 Christmas shopping season. The collection, Batman: A Expiry in the Family, shipped on December 5, 1988, less than a calendar week after Batman #429.[four] A 2009 hardcover reprint included Wolfman, Pérez, and Aparo's 1989 sequel storyline, "A Lonely Place of Dying", which introduced Todd'south successor Tim Drake.[15] A hardcover deluxe edition was published in April 2021.[16]

For many years, the version of Batman #428 in which Todd lives remained unpublished, though the pages remained housed in DC'due south archives in Burbank, California.[17] Batman Annual #25, published in March 2006, used i of the alternate pages Aparo had prepared;[16] some panels were released by Les Daniels in his book Batman: The Complete History (1999) and by Polygon announcer Susana Polo in 2020.[17] In March 2020, the DC Daily spider web prove unveiled all of the pages to the public for the get-go fourth dimension,[18] and the artwork was published in the 2021 palatial edition.[16]

Synopsis [edit]

While eavesdropping on a child pornography ring and pending law backup in Gotham Urban center, Jason Todd (Robin) ignores Batman'due south orders and attacks the criminals. Batman chastises Todd and asks if he considers crimefighting a game; Todd replies that life is a game. At Wayne Manor, Batman decides Todd is emotionally unstable and relieves him of his duties every bit Robin; an enraged Todd storms off. Meanwhile the Joker, Batman's archenemy, escapes from Arkham Asylum. Batman discovers that he has obtained a nuclear weapon and plans to sell information technology to terrorists, and tracks him to state of war-torn Lebanon.

Walking through his one-time neighborhood, Todd meets a friend of his late parents, who gives him his father'due south old documents. Todd discovers that his mother'southward name on his nascence certificate is blotted out, and that her beginning initial is "S", not "C" as in Catherine Todd, the adult female he knew as his mother. Todd concludes that Catherine was his stepmother and decides to search for his biological mother. He uses the Batcomputer to track iii possible individuals to the Heart Due east and Africa. Todd travels to Lebanon, where he and Batman reunite. The 2 foil an try by terrorists to destroy Tel Aviv using a nuclear missile purchased from the Joker. Batman agrees to help Todd detect his mother, and Todd interrogates his showtime doubtable, Mossad agent Sharmin Rosen. His next suspect is Batman's old acquaintance Lady Shiva, who says she is non Todd'south mother after she is administered a truth serum by the duo.

Batman and Todd travel to Ethiopia and confirm that Todd's mother is Sheila Haywood, an help worker; Todd has an emotional reunion with her. However, the Joker discovers that Haywood had performed illegal surgeries on teenagers in Gotham and has been blacklisted as a medical practitioner. The Joker uses this information to blackmail her into giving him the medical supplies her bureau has stockpiled in a warehouse. He sells them on the black market and stocks the warehouse with Joker venom, which will kill thousands of people. Haywood has besides been embezzling from the aid agency and, as part of a cover-up, hands Todd, in his Robin costume, over to the Joker. The Joker beats Todd with a crowbar and restrains him and Haywood in the warehouse with a fourth dimension bomb. Todd throws himself on the bomb to shield Haywood as the warehouse explodes. Batman arrives also late to salvage them and Todd and Haywood dice from their injuries.

Traumatized, Batman takes Todd and Haywood's remains to Gotham and holds a burial with Alfred Pennyworth, Commissioner James Gordon, and Barbara Gordon. Batman blames himself for Todd's decease and resolves to carry on alone, rejecting Pennyworth'due south suggestion to involve Dick Grayson, the first Robin. The Joker meets with Ayatollah Khomeini, who offers him a office in the Iranian regime. The Joker leaves a warehouse containing the corpses of his henchmen and the accost of the UN Headquarters for Batman. Equally Batman waits exterior the UN building, Superman appears and tries to convince Batman to leave. The Joker is Iran'southward representative to the Un and volition be giving a speech communication on the floor of the General Associates, and any confrontation between Batman and him could start a diplomatic incident.

During his speech, the Joker attempts to poisonous substance the entire chamber with Joker venom, but Superman intercepts the gas. Batman pursues the Joker onto a helicopter sent by his sponsors. During the resulting struggle, one of the Joker's henchmen opens fire with a automobile gun and shoots the pilot, crashing the helicopter into the bounding main. Superman saves Batman, but the Joker'south trunk is not found. Batman laments that everything betwixt him and the Joker ends unresolved.

Reception [edit]

Initial [edit]

Editor Dennis O'Neil (pictured in 2012) proposed that DC allow fans to decide if Todd was to die.

The first iii capacity of "A Decease in the Family" sold out speedily,[4] and co-ordinate to Starlin, the storyline was DC'southward bestselling comic of 1988.[19] The storyline drew coverage in newspapers including Us Today, Reuters, and the Deseret News.[xx] [21] Many reports did not mention that Todd was not the original Robin.[twenty] As an editor at Marvel Comics, O'Neil had received angry mail service from fans when characters such as Phoenix and Elektra were killed, then he was prepared for reader backlash to Todd's decease. Even so, "A Death in the Family" created much more controversy, as Robin was i of DC's most iconic characters and the Marvel deaths had occurred during a period of recession in comics.[20]

O'Neil spent the days following Batman #428'south publication "doing aught but talking on the radio. I thought it would go us some ink hither and at that place and maybe a couple of radio interviews. I had no idea—nor did anyone else—it would have the consequence it did."[i] Afterward three days, Peggy May, DC's publicity director, ordered O'Neil to cease talking to the media. She also barred anyone from discussing the story on television. Though initially confused, O'Neil came to appreciate May's order because he did not desire the public to see him equally "the guy who killed Robin".[1] Assistant editor Dan Raspler was chastised by DC's so-executive vice president Paul Levitz for referring to "A Expiry in the Family unit" as a "stunt" in an interview.[4]

Todd'southward decease divided fans at the fourth dimension.[8] Many readers celebrated, some hoping information technology meant that Grayson could go Robin again. Others lamented how bloodthirsty comic book readers were.[8] [22] O'Neil and the Batman team received hate mail and angry phone calls; co-ordinate to O'Neil, the calls ranged from "'You bastard,' to bawling grandmothers saying, 'My grandchild loved Robin and I don't know what to tell him.'"[i] Frank Miller was disquisitional, calling the story "the most contemptuous thing [DC] has ever done ... fans tin call in to put the axe to a little boy's head. To me the whole killing of Robin thing was probably the ugliest matter I've seen in comics".[23] NPR cultural critic Glen Weldon establish the criticism to be ironic, as it was Miller who came upward with the idea of the Joker killing Todd in The Dark Knight Returns.[24]

Retrospective [edit]

Critics accept agreed with the determination to kill Todd in retrospect.[viii] [24] [25] Sims wrote that killing Todd was "unquestionably the right decision" and made for a far better story.[viii] He opined that allowing the Joker to defeat Batman enhanced both characters: the Joker became "a deadly threat... whose actions accept lasting consequences", while Batman had "a motivating loss at a fourth dimension when new readers were coming in".[eight] Hilary Goldstein of IGN and Jamie Hailstone of Den of Geek praised the story'southward handling of Todd'south death for its emotion and portraying the dangers of superheroics.[25] [26]

Retrospective reviewers have faulted "A Decease in the Family unit" for its plot.[25] [26] [27] Hailstone described "A Death in the Family" as "the ultimate 80s epic": "brasher than Top Gun, louder than Blob Hogan and more than implausible than The A-Team".[26] Both Hailstone and Goldstein establish the plot hard to believe,[25] [26] and Hailstone said that it veers into nonsense when the Joker is appointed as an ambassador.[26] Charles Prefore, writing for Screen Rant, said the story "tin't determine if it wants to exist fun or dark"; while Todd's torture and expiry at the easily of the Joker is quite somber, elements like the "globetrotting nature of the story" and the Joker becoming an administrator for Iran are evocative of the goofy Silver Age of Comic Books. Prefore said the story's grim moments, which caused "A Death in the Family" to gain a reputation as one of the darkest Batman stories, overshadow the residuum of its outlandishness.[27]

"A Death in the Family" remains a popular story amongst readers,[22] and despite their reservations over the plot, critics still accounted it worth reading.[25] [26] [27] Hailstone chosen the story a "guilty pleasure" that, while non equally groundbreaking equally "Year One" or Batman: Son of the Demon (1987), was entertaining still,[26] and Prefore summarized it as "a practiced read if y'all don't mind all the strangeness".[27] Publications ranking information technology amid the best Batman stories include IGN and Circuitous in 2014,[28] [29] and GamesRadar+ and Screen Rant in 2021.[30] [31] Sean T. Collins of Rolling Stone ranked it amongst the xv Batman stories he considered "essential" to agreement the graphic symbol, praising Aparo'due south fine art and how Starlin characterizes the Joker.[32]

Literary analysis [edit]

Despite Robin's status as i of the most famous sidekicks in comic book history, there has been niggling literary assay of "A Expiry in the Family".[33] Co-ordinate to literary critic Kwasu Tembo, it is generally only discussed "equally either a instance study within a broader give-and-take of Batman's ethics, or equally a example study of DC'due south editorial decisions and socio-historical appointment with its readership".[34] The story'due south bulletin is that Batman cannot save everyone,[8] and information technology portrays Todd as a tragic figure whose sympathetic journeying ends in death.[35] Tembo contended that the death leaves the reader to ponder Todd'southward nature as "Batman's greatest failure, as an orphan betrayed, and/or as a careless and overzealous lost boy who reaped what he had and then impulsively and thoughtlessly sown".[36]

Tembo theorized that Todd's death, as voted for by readers, "can be more thoroughly understood equally a complex form of scapegoating", comparable to a public execution.[37] Todd was unpopular considering he struggled to live up to the standard of his predecessor Grayson, which made him a "bad" Robin.[38] This created jealousy among readers, who concluded that Todd was unfit to be Robin.[39] Citing René Girard's theory of mimetic desire, Tembo wrote that O'Neil'due south decision to permit fans determine Todd's fate created a "mimetic crisis" because readers "could now not merely influence [Todd'southward] existence in the story world, only in existence given this power, compete against him".[xl] Readers instead saw themselves every bit more fit to be Batman'due south partner; past voting to kill Todd, they thought they were helping Batman.[41] Tembo points out that the closeness of the vote indicates that fans may not have despised Todd every bit much as commonly believed. Fans who voted to save Todd may accept voted to preserve the archetype status quo, or because they found the Joker'due south murdering a child during an emotional menses in his life unsettling.[37]

Depiction of Islam [edit]

As an Iranian ambassador, the Joker wears a traditional Arab headdress and robes although Iran is non an Arab country.[42] Art past Jim Aparo, Mike DeCarlo, and Adrienne Roy

"A Death in the Family" has been criticized as Islamophobic for its portrayal of Arab terrorists. The terrorists are portrayed as anti-American, anti-Israel fanatics who seek to violently take over the Western earth.[43] [44] They are referred to as "bandits-in-bedsheets" and depicted as unshaved and always holding weapons, while Jamal, the terrorist leader, is overweight and perpetually sneering.[45] In a 1991 study of Arab terrorist depictions in comic books, Jack Shaheen wrote that "A Death in the Family" conflates Arabs, Muslims and terrorists, and equates them to the Joker, an insane supervillain.[45] Jehanzeb Dar and Shaheen cited the Joker'due south spoken language to the General Assembly as a specially egregious example of Islamophobia in "A Decease in the Family unit".[45] Earlier he attempts to toxicant the sleeping room, the Joker gloats:

I am proud to speak for the great Islamic republic of iran. That country's current leaders and I have a lot in mutual. Insanity and a dandy honey of FISH. But unfortunately we share a mutual problem. We get NO RESPECT. Anybody thinks of Islamic republic of iran as the home of the TERRORIST ZEALOT! They say even worse things about ME, would yous believe? We've both suffered unkind ABUSE AND BELITTLEMENT! WELL, WE AREN'T GOING TO TAKE It ANYMORE!! Yous'll no longer exist allowed to kick us around. In fact, you aren't going to be able to kick ANYONE effectually ever again!

—The Joker, Batman #429

Dar described the Joker's spoken language equally blatant Islamophobia disguised as humor.[42] Shaheen and Dar argued "A Decease in the Family unit" promotes the idea of "Them vs. Us", pitting the Arab and Western worlds confronting each other equally diametrically opposed in values.[42] [45] The story contains errors in its depiction of the Eye East. Starlin writes Batman as speaking Farsi, the Persian language, in Beirut (where Arabic is actually the normally spoken communication), and the Joker dons a traditional Arab headdress and robes every bit the Iranian ambassador, although Iran is non an Arab country.[42] Dar concluded that "[Starlin]'s and [DC]'s disregard for cultural, religious, and political accuracy simply points to a rough and racist generalization: Arabs, Iranians, and Muslims are all the 'same' and 'detest' the West."[42]

Legacy [edit]

"A Expiry in the Family" was part of the American comic book industry'due south trend towards "grim and gritty" comics in the belatedly 1980s,[24] [22] and is remembered every bit ane of DC'south near controversial storylines.[46] [47] Chris Snellgrove of Looper described the scenes depicting Todd's torture and death—with the Joker covered in his blood— as "one of the near disturbing moments in the publisher's long history".[48] DC editors took the lessons they learned from the controversy and used media coverage for publicity when killing off major characters in the future,[49] such every bit Superman in "The Death of Superman" (1992–1993).[l]

Although "A Death in the Family unit" sold well, it harmed Starlin's continuing at DC. DC's licensing department was infuriated over the expiry because of the amount of merchandise—such equally lunchboxes and pajamas—that diameter Robin'southward likeness. According to Starlin, "everybody got mad, and they needed somebody to arraign—so I got blamed."[19] Piece of work quickly declined for him, and within vi months he departed DC and returned to Marvel Comics, where he wrote The Infinity Gauntlet (1991).[11]

Outcome on future stories [edit]

"A Death in the Family" is regarded as one of the most important Batman comics for its result on futurity Batman stories.[51] [52] The story contradistinct the DC Universe: instead of killing anonymous bystanders, the Joker murdered a core grapheme in the Batman fiction.[53] Alongside The Killing Joke (which featured Barbara Gordon, Batgirl, beingness shot in the breadbasket and paralyzed) and the success of the 1989 Batman picture show, "A Death in the Family unit" pushed the Batman mythos in a darker direction.[iv] Information technology portrayed Batman equally more violent and emotional post-obit Todd's death, and for the next decade of comic book canon, he was haunted by his failure to save him.[54] Conway felt that the storyline allowed for "the entrance of the existent 'Dark Knight', the idea of Batman as the pitiless enforcer of Gotham".[55] When the DC Universe canon was rebooted during DC's 2011 New 52 reboot, the events of "A Death in the Family unit" were left intact because DC editors deemed it too of import.[56]

Todd was likely to be replaced as Robin regardless of his survival. O'Neil wanted to wait a year for a successor, just DC management demanded a new Robin immediately. O'Neil and Wolfman began developing the graphic symbol of Tim Drake, who debuted in the 1989 storyline "A Lonely Place of Dying" past Wolfman, Pérez, and Aparo. O'Neil arranged for a nuanced introduction that explained why Batman would demand a new sidekick later on Todd's expiry, and Drake was designed to entreatment to both Todd's fans and detractors.[58] Drake proved popular and starred in several express series and a 1993–2009 ongoing serial,[58] [59] until he was replaced by Damian Wayne in 2009.[60] Wayne shared Todd's willingness to go against Batman'southward wishes and use lethal forcefulness;[61] Grant Morrison and Frazer Irving'southward Batman and Robin #thirteen (2010) featured a scene in which Wayne beat the Joker with a crowbar, paralleling Todd's murder.[62]

Throughout the 1990s and early on 2000s, Todd'southward death was one of the few comic book deaths that remained unreversed. Different traditional comic volume deaths, Todd's was intended to stay permanent; at the time of "A Decease in the Family"'s publication, O'Neil said that "it would be a really sleazy stunt to bring him dorsum".[63] A pop adage amidst comic book fans was that in comics, no characters stayed dead except Bucky Barnes, Uncle Ben, and Todd.[64] (Marvel would revive Barnes in 2004 equally the Winter Soldier.[65]) Todd'southward revival was first teased in the "Hush" (2002–2003) storyline by Jeph Loeb and Jim Lee, which features Clayface impersonating an undead Todd to taunt Batman.[54] Later writer Judd Winick read "Hush", he wondered why DC never revived Todd.[8] Winick and artist Doug Mahnke's 2004–2006 storyline "Nether the Hood" revived him as the murderous vigilante Cherry-red Hood; the in-universe caption for Todd's revival was that he was restored to life after Superboy-Prime punched the wall of a pocket dimension.[54] Todd eventually re-joined Batman'south supporting bandage equally an "on-again, off-over again marry",[8] and starred in the series Cherry-red Hood and the Outlaws (2011–2021).[66] Despite his resurrection, in 2020 journalist Susana Polo noted Todd was nevertheless about famous for dying in "A Death in the Family".[17]

In other media [edit]

Bruce Timm and Paul Dini considered adapting "A Death in the Family" for Batman: The Blithe Series (1992–1999), merely decided it was too vehement. Instead, they omitted the Todd character and incorporated some of his characteristics in Drake.[67] The story was somewhen adapted in the comic book sequel Batman: The Adventures Continue (2020), written by Dini and Alan Burnett and penciled past Ty Templeton. In the Adventures Continue adaptation, the Joker and Harley Quinn kidnap Todd, and the Joker beats him with a crowbar with intent to kill him. Harley objects to killing a child and finds Batman, who arrives as the warehouse is engulfed in flames due to hydrogen tanks. A wounded Todd begs for Batman to kill the Joker, simply Batman instead tries to salve him; Todd attempts to stop Batman but knocks over more hydrogen tanks, causing the explosion and his apparent death.[68]

Elements from "A Expiry in the Family" were incorporated in the 2010 DC Universe Animated Original Movies moving-picture show Batman: Nether the Red Hood, an adaptation of "Nether the Hood" directed by Brandon Vietti.[69] [70] In the motion-picture show, Ra's al Ghul (Jason Isaacs) hires the Joker (John DiMaggio) to distract Batman (Bruce Greenwood) and Todd (Jensen Ackles) while he destroys Europe's financial districts. They follow the Joker to Bosnia, where he kills Todd in like manner to "A Death in the Family".[71] An interactive flick accommodation, Batman: Death in the Family, was released in 2020. The film is a sequel to Nether the Ruby Hood, Vietti over again directing and the cast, with the exception of Vincent Martella replacing Ackles, reprising their roles.[70] [72] Similar to the voting system from the comic, the film allows viewers to determine if Todd lives or dies, leading to different scenarios that see him get Cherry Hood, Hush, or Red Robin.[73]

"A Decease in the Family unit" is referenced in the DC Extended Universe (DCEU), a shared universe of superhero films based on DC characters. Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice (2016) features a damaged Robin suit on display in the Batcave,[74] while Suicide Squad (2016) reveals that Harley Quinn (Margot Robbie) helped the Joker (Jared Leto) murder him.[75] Zack Snyder'south Justice League (the 2021 director's cut of Justice League (2017)) features a scene in which the Joker mocks Batman (Ben Affleck) for Robin's expiry.[76] Though Warner Bros. and Suicide Squad managing director David Ayer stated that the dead Robin was Todd,[77] [78] Batman v Superman director Zack Snyder afterwards said he had intended information technology to be Grayson, dissimilar "A Death in the Family".[78] Snyder had planned to explore Robin's death in detail in his Justice League sequels before their cancellation.[79] Before the release of Zack Snyder's Justice League, Snyder proposed a comic book prequel to Batman v Superman that depicted Robin's death, only DC turned information technology down.[80]

In "Emperor Joker", a 2010 episode of Batman: The Brave and the Bold (2008–2011), a fourth wall-breaking Bat-Mite (Paul Reubens) references "A Decease in the Family" and the 900 number, and Batman is briefly seen cradling a expressionless Robin.[81] Todd'south portrayal in the video game Batman: Arkham Knight (2015) was inspired by "A Expiry in the Family".[82] The DC Universe and HBO Max streaming goggle box serial Titans (2018–present) features Todd every bit a fundamental character portrayed past Curran Walters. After the second season episode "Deathstroke" (2019) ended on a cliffhanger with Deathstroke (Esai Morales) attempting to kill Todd, DC Universe held a poll in which fans could vote to determine Todd's fate. The poll was only intended as a reference to "A Death in the Family", and had no result on the series.[82] Elements from "A Expiry in the Family unit" were incorporated in the tertiary flavour of Titans, which premiered in 2021.[83]

Notes [edit]

- ^ The DC Universe is the shared universe that most of DC's comics, including those related to Batman, accept place inside.

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h Pearson Uricchio 1991, p. 18–32.

- ^ Weldon 2016, p. xxx.

- ^ Weldon 2016, p. 124.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l one thousand n o p q r s t u Grunenwald, Joe (November 29, 2018). "The Lives and Death of Jason Todd: An Oral History of The Second Robin and A Death in the Family unit". The Beat. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- ^ a b Weldon 2016, p. 126.

- ^ Thompson 1987, p. 23-41.

- ^ Weldon 2016, p. 147.

- ^ a b c d e f thousand h i j Sims, Chris (December i, 2017). "That's What'south Upwardly: How Jason Todd Became One Of DC'south Most Hated Characters". Looper. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- ^ a b Franklin 2011, p. 67-76.

- ^ a b c Greenfield, Dan (Dec 20, 2014). "Denny O'Neil: Getting Rid of Robin - Twice". 13th Dimension. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved June 24, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Avila, Mike (October 31, 2018). "Watch: Jim Starlin on creating Thanos, killing Robin, and seeing his characters on the big screen". SyFy Wire. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- ^ Weldon 2016, p. 147–148.

- ^ a b c Weldon 2016, p. 148.

- ^ a b c d e f 1000 h F+W 1988, p. Comprehend, 3.

- ^ Batman A Decease in the Family (HC (2009 DC Library) ed.). DC Comics. 2009. Archived from the original on 2017-07-24. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- ^ a b c Grunenwald, Joe (November 13, 2020). "New Batman: A Death in the Family hardcover to include full alternate artwork in which Jason Todd lived". The Vanquish. Archived from the original on March 3, 2021. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- ^ a b c Polo, Susana (March x, 2020). "The most tragic moment in Batman's history virtually looked like this". Polygon. Archived from the original on June nine, 2021. Retrieved June 12, 2021.

- ^ Grunenwald, Joe (March 27, 2020). "DC finally reveals the alternate Batman: A Death in the Family art in which Jason Todd lived". The Shell. Archived from the original on June 25, 2021. Retrieved June twenty, 2021.

- ^ a b Belkin, Mark (Apr 26, 2018). "Jim Starlin talks with Mark Belkin about DC in the 80s". DC in the 80s. Archived from the original on July 14, 2021. Retrieved July xiii, 2021.

- ^ a b c Weldon 2016, p. 149.

- ^ "Holy Popcorn! Readers Zap Boy Wonder". Deseret News. Oct 27, 1988. Archived from the original on June 27, 2021. Retrieved June 26, 2021.

- ^ a b c Calamia, Kat (May 26, 2020). "Revisiting Batman's 'a Death in the Family' controversial fan vote". GamesRadar+. Archived from the original on July 13, 2021. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ Pearson Uricchio 1991, p. 33–46.

- ^ a b c Weldon 2016, p. 150.

- ^ a b c d e Goldstein, Hilary (June 9, 2005). "Batman: A Death in the Family Review". IGN. Archived from the original on June thirty, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ a b c d eastward f g Hailstone, Jamie (November 24, 2008). "Batman: A Expiry In The Family". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on June 28, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Prefore, Charles (June 21, 2020). "The Expiry of Robin Was Weirder Than You Recall". Screen Bluster. Archived from the original on July 10, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ Yehl, Joshua; Goldstein, Hilary (April 9, 2014). "The 25 Greatest Batman Graphic Novels". IGN. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ Serafino, Jason (May 1, 2014). "The 25 All-time Batman Comics Of All Fourth dimension". Complex. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ Lydon, Pierce (July vii, 2021). "Best Batman stories of all fourth dimension". GamesRadar+. Archived from the original on Apr 9, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ Lealos, Shawn S. (May 24, 2021). "14 Of Batman's All-time Comic Book Arcs Of All Time, Ranked". Screen Rant. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ Collins, Sean T. (July 23, 2012). "The Nighttime Knight Reads: xv Essential Batman Graphic Novels". Rolling Rock. Archived from the original on May 10, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ Tembo 2021, p. 189.

- ^ Tembo 2021, p. 203.

- ^ Tembo 2021, p. 201.

- ^ Tembo 2021, p. 202.

- ^ a b Tembo 2021, p. 190.

- ^ Tembo 2021, p. 196.

- ^ Tembo 2021, p. 207.

- ^ Tembo 2021, p. 207, 209.

- ^ Tembo 2021, p. 209.

- ^ a b c d east Dar 2010, p. 102.

- ^ Dar 2010, p. 101.

- ^ Shaheen 1994, p. 123.

- ^ a b c d Shaheen 1994, p. 124.

- ^ Webber, Tim (August 18, 2018). "25 Controversial Changes That Left The DC Universe (And Fans) Shook". Comic Volume Resources. Archived from the original on July 14, 2021. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ Leroy, Kath (June 24, 2020). "DC: 10 Controversial Stories That Angered Fans". Comic Book Resource. Archived from the original on July 14, 2021. Retrieved July thirteen, 2021.

- ^ Snellgrove, Chris (March ii, 2017). "The Virtually Disturbing Moments In DC Comics History". Looper. Archived from the original on Oct 31, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ Weldon 2016, p. 149–150.

- ^ Weldon 2016, p. 192.

- ^ Parker, Jamie (December 26, 2020). "Batman: 10 Most Important Stories (In The Comics)". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on July 12, 2021. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- ^ Saavedra, John (April 27, 2018). "The 25 Most Important Batman Stories Ever Told, A CBR Ranking". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on July 12, 2021. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- ^ Manning 2011, p. 108.

- ^ a b c Eason, Brian Chiliad. (June 11, 2007). "DC Flashback: The Life and Death and Life of Jason Todd". Comic Book Resource. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved June 22, 2021.

- ^ Volo, Kevin (June 18, 2017). "Episode 38: Jason Todd with Gerry Conway Interview". The Heroes, Villains and Sidekicks Bear witness. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved June 22, 2021.

- ^ Rogers, Vaneta (June 15, 2011). "Harras, Berganza: DCnU Will Go on Much of DC History Intact". Newsarama. Archived from the original on December xix, 2013. Retrieved July v, 2021.

- ^ a b Rogers, Vaneta (February 24, 2011). "Why They Endure: Pros On Tim Drake's Rise Upward the Bat-Ranks". Newsarama. Archived from the original on May four, 2013. Retrieved July vii, 2021.

- ^ "Robin (1993-2009)". DC Comics. Archived from the original on July 15, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2021 – via ComiXology.

- ^ Buxton, Marc (December 27, 2015). "From Dick to Damian: A History of Robin, Batman's Superstar Sidekick". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on July xv, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ Hernandez, Danny (December 6, 2019). "Robin War: 5 Reasons Why Jason Todd Is The Better Robin (& five It's Damian Wayne)". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on July 11, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- ^ Sims, Chris (July 8, 2010). "Roundtable Review: 'Batman and Robin' #13". ComicsAlliance. Archived from the original on July 15, 2021. Retrieved July xv, 2021.

- ^ Taylor 2008, p. fourteen.

- ^ Williams, Owen (May ix, 2014). "No One Stays Dead In Comics: sixteen Superhero Deaths And How Long They Lasted". Empire. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ^ Riesman, Abraham (March 19, 2021). "SUPERHEROES UPDATED MAR. nineteen, 2021 The Story Behind Bucky'due south Groundbreaking Comic-Book Reinvention Every bit the Winter Soldier". Vulture. Archived from the original on May vii, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2021.

- ^ Esposito, Joey (September 16, 2011). "Red Hood and the Outlaws #ane Exclusive Preview". IGN. Archived from the original on July 12, 2021. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- ^ Altieri, Kevin; Dini, Paul; Kirkland, Boyd; Radomski, Eric; Riba, Dan; Timm, Bruce (2004). Robin Rise: How the Boy Wonder's Grapheme Evolved (Interview with Batman: The Blithe Series staff). Warner Bros. Event occurs from 6:04–six:35.

- ^ Sawan, Amer (September 14, 2020). "Batman Reveals What the Animated Series Joker Did to Jason Todd". Comic Volume Resources. Archived from the original on June 29, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ White, Cindy (July 8, 2010). "Batman: Nether the Red Hood Blu-ray Review". IGN. Archived from the original on Apr vi, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ a b Dar, Taimur (Oct xiii, 2020). "Interview: Finding heart in horror with the Batman: Death in the Family bandage/crew". The Beat. Archived from the original on January xx, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ Rector, Seth (September 7, 2020). "Batman: Nether The Blood-red Hood - x Biggest Differences Between The Comic & Movie". Screen Bluster. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ Motamayor, Rafael (Nov 10, 2020). "The first cull-your-own-adventure Batman film made the wrong decisions". Polygon. Archived from the original on July ix, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ Trumbore, Dave (October 14, 2020). "'Batman: Death in the Family unit' Review: The Interactive Movie Is WB Animation'southward Virtually Ambitious in Years". Collider. Archived from the original on May 31, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ Chapman, Tom (November eighteen, 2020). "Batman five Superman Easter egg reveals Robin'south brutal manner of death". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on July ix, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ^ Grant, Stacey (August 8, 2016). "Did You Catch Harley Quinn'due south Connection To Robin In Suicide Squad?". MTV. Archived from the original on October 9, 2017. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ^ Breznican, Anthony (March 18, 2021). "Zack Snyder Explains That Enigmatic Justice League Ending". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on March 19, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ^ Grebey, James (August 8, 2016). "A 'Suicide Squad' Easter egg may answer 1 of the biggest questions from 'Batman 5 Superman'". Business Insider . Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- ^ a b Ridgely, Charlie (November 18, 2018). "'Batman five Superman' Managing director Zack Snyder Confirms Identity of Robin in the Film". ComicBook.com. Archived from the original on March 25, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ^ O'Connell, Sean (March 22, 2021). "Joker And Robin Would Have Had A 'Good Fight' In Zack Snyder'southward Justice League Sequel And At present I Want Information technology". CinemaBlend. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ^ Guilherme, Andre (February 17, 2021). SnyderCutBR | Entrevista Zack Snyder (Completa). SnyderCutBR • Liga da Justiça de Zack Snyder – via YouTube.

- ^ Nadel, Nick (October 26, 2010). ""A Death in the Family" Gets the "Batman: The Brave and the Bold" Treatment". ComicsAlliance. Archived from the original on 2017-08-01. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b Schedeen, Jesse (Oct 10, 2019). "Titans Poll Reveals How Many Fans Still Want Jason Todd'south Robin Dead". IGN. Archived from the original on May 31, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ^ Venable, Nick (June 17, 2021). "Titans Season 3 Kickoff Trailer Immediately References The Joker's Arrival For A Death In The Family Arc". CinemaBlend. Archived from the original on July 4, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

Bibliography [edit]

- Dar, Jehanzeb (2010). Kincheloe, Joe L.; Steinberg, Shirley R.; Stonebanks, Christopher D. (eds.). "Holy Islamophobia, Batman! Demonization of Muslims and Arabs in Mainstream American Comic Books". Counterpoints. Switzerland: Peter Lang. 346: 99–110. ISSN 1058-1634.

- Franklin, Chris (May 2011). "Dead on Demand: Jason Todd, the 2d Robin". Back Issue!. Raleigh: TwoMorrows Publishing. 1 (48): 67–76. ISSN 1932-6904.

- "How, why, and when Robin died: A year to the life or death of Robin, or How Jason's fate was decided in more 365 days". Comics Buyer'due south Guide. New York Urban center: F+W. 1 (789): Encompass, 3. 30 December 1988. ISSN 0745-4570.

- Manning, Matthew K. (2011). The Joker: A Visual History of the Clown Prince of Crime. Milan: Universe Publishing. ISBN978-0-7893-2247-0.

- Pearson, Roberta Eastward.; Uricchio, William, eds. (1991). The Many Lives of The Batman: Critical Approaches to a Superhero and His Media. London: BFI Publishing. pp. 18–32. ISBN0415903475.

- Shaheen, Jack G. (1994). Browne, Ray B. (ed.). "Arab images in American comic books". The Journal of Popular Culture. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. 28 (one): 123–133. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1994.2801_123.x. ISSN 0022-3840.

- Taylor, Robert Brian (February 9, 2008). "Keeping Information technology Real in Gotham". In O'Neil, Dennis; Wilson, Leah (eds.). Batman Unauthorized: Vigilantes, Jokers, and Heroes in Gotham Metropolis. Dallas: Smart Popular. pp. vii–15. ISBN978-1933771304.

- Tembo, Kwasu (July 25, 2021). "72 Votes: Theorizing the Scapegoat Sidekick in Batman: A Death in the Family unit". In Andrew, Lucy; Saunders, Samuel (eds.). The Detective's Companion in Crime Fiction: A Report in Sidekicks. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 189–213. ISBN978-3-030-74989-vii.

- Thompson, Kim (June xv, 1987). "Watching the Detectives: An Interview with Max Allan Collins". Amazing Heroes. Seattle: Fantagraphics Books. 1 (119): 23–41. ISSN 0745-6506.

- Weldon, Glen (2016). The Caped Crusade: Batman and the Rise of Nerd Culture. New York City: Simon & Schuster. ISBN978-ane-4767-5669-1.

External links [edit]

- Official website

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Death_in_the_Family_(comics)

0 Response to "Law and Order "a Death in the Family""

Post a Comment